Reposted from the Dallas Morning News 5/10/15 by Ralph Strangis

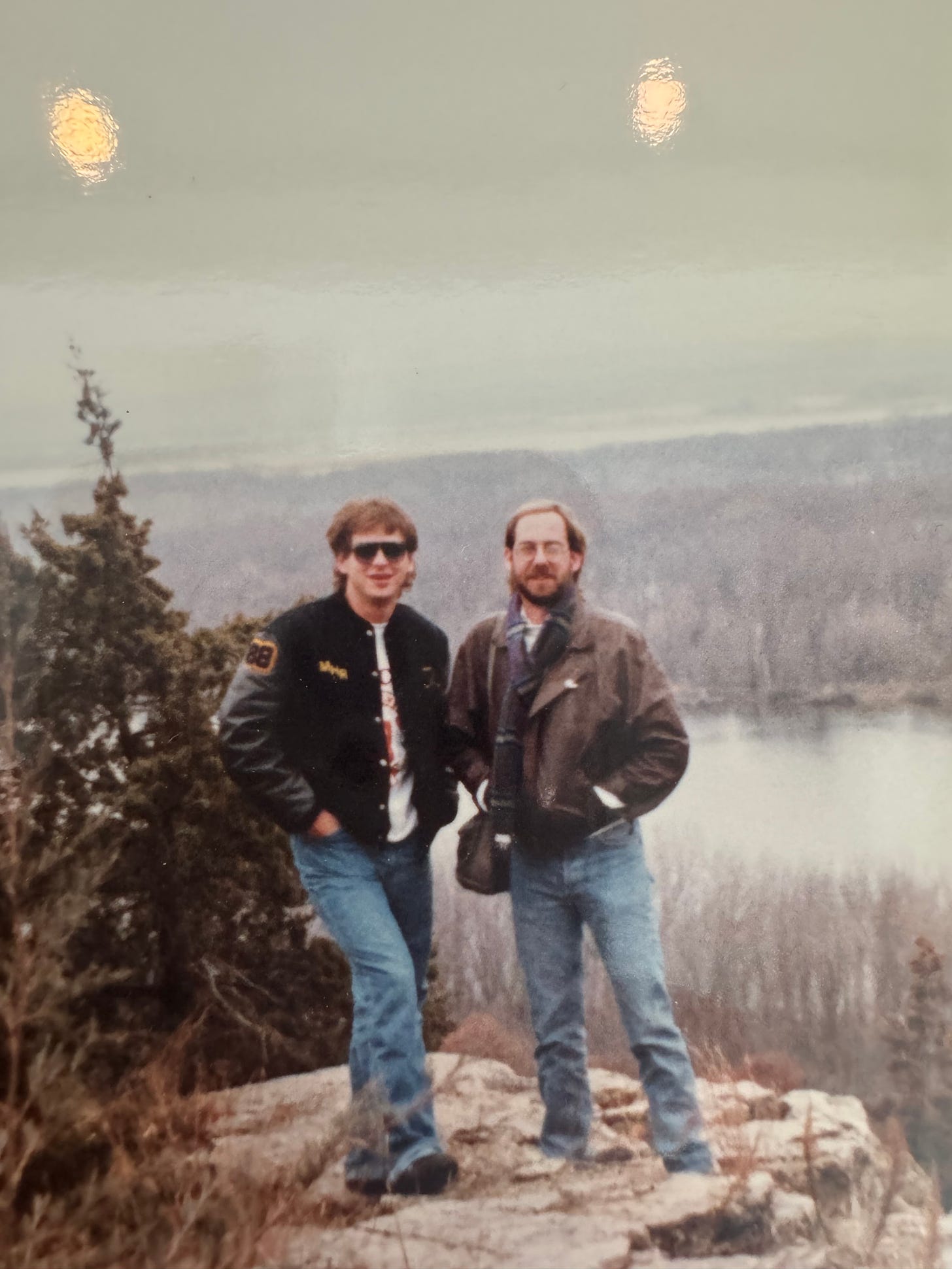

Ralph and Hollywood collide in the early 80’s…

It’s a gray and cool Sunday morning in late May of ’83 and I’m knocking on John Ridgway’s Santa Monica apartment door, hoping he remembers our booze-fueled talks a few months earlier in the Hotel Cosmos bar in Moscow. He’d better remember, or I’ve just dropped out of college and driven 2,000 miles for nothing.

My two-toned, beige-on-beige pickup truck with the camper lid and yellow fog lights is parked on the street and out of my eyesight. There isn’t much inside, but it’s all I’ve got in the world, especially considering — if you wanna know the truth about it — the truck isn’t really mine to begin with.

Ridgway, nine years my senior, is gaunt and slight, with a well-groomed beard and wire-rimmed spectacles and an overall look that screams “Hollywood Producer Guy.” And though you’d never confuse him with an athlete, when he opens the door he’s wearing his Entertainment Tonight team softball uniform for that day’s game.

“Well, Roscoe … you made it,” he says with equal measures of surprise and admiration. He calls me Roscoe and, for the life of me, I can’t remember why.

“Yep. Here I am. When do we start?”

I’m like that. I’ve always been like that, and I know not everybody is wired like that. You know, the kind of guy who leaps before checking to see if the parachute is even in the bag. What the hell? My life, my rules. Never had much use for authority or anybody else’s notion of what things should look like. Always wondering about a world where you go fishing only three days a year. Always questioning things we do just ’cause we’ve always done them. Don’t like explaining myself to anybody, either.

Gotta have a college degree, everybody tells me. Really? Naw. Never really got on with college. Never missed calling a game or working a radio shift, but hardly made it to biology class. So I don’t have a degree. Dropped out of college four times from three separate institutions. Anyways, even the journalism profs tell you that it’s small market first, then midsized market, and then if you’re lucky, maybe you’ll forget all this stardom crap and find a good radio sales job. Not true. Doesn’t have to be, anyway.

Seems like the world — come hell or high water — wants its pound of flesh, and it’s up to me whether it gets it. Most tethers are applied and fastened by the wearer. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t scared sometimes, but it has never stopped me from taking a big chance to do something epic. Let me explain.

So, one night way back in River Falls, Wis., I’m working the late-late shift at the campus radio station when one of the few profs I actually like comes into the studio and tells me I should go on his Soviet Media Tour with students and industry pros from around the country. A guy like me doesn’t need to be asked twice. That’s where I meet Ridgway. That’s where we have adventures in Cold War Russia. That’s where he says, late one night, “Hey, Roscoe, you ever get tired of that college thing, come see me in L.A, and I’ll put you to work.”

Even after my time in LA with Ridgway, which sends me crawling back to my home state with nothing but a duffel bag and a nickel-a-week cocaine habit, I still know I’m going to get through it and do something epic. I had some great mentors in this regard.

Ridgway’s buddy Ben Goddard, a.k.a. “Dr. Bud Pollard,” comes to see me before I leave Hollywood and tells me a story.

“Ralph, Ralph, Ralph … when I was about your age, I started an ad agency and did really well all the way up to the point that I snorted the entire company and my new Mercedes up my nose. I was in debt and had no money and no company anymore.” “What did you do?” “What could I do, Ralph? … I went skiing in Vail for two weeks.”

Greatest answer ever. EVER! Most people who tell a story like that go on to tell you about the laborious climb through shame and fear and sucking up to the naysayers and the years spent digging out. Which we all know is eventually what happens. But instead of rubbing it in my face, Ben restores my worldview. Life gives you lemons, turn ’em in for limes — they go way better with the chicken salad.

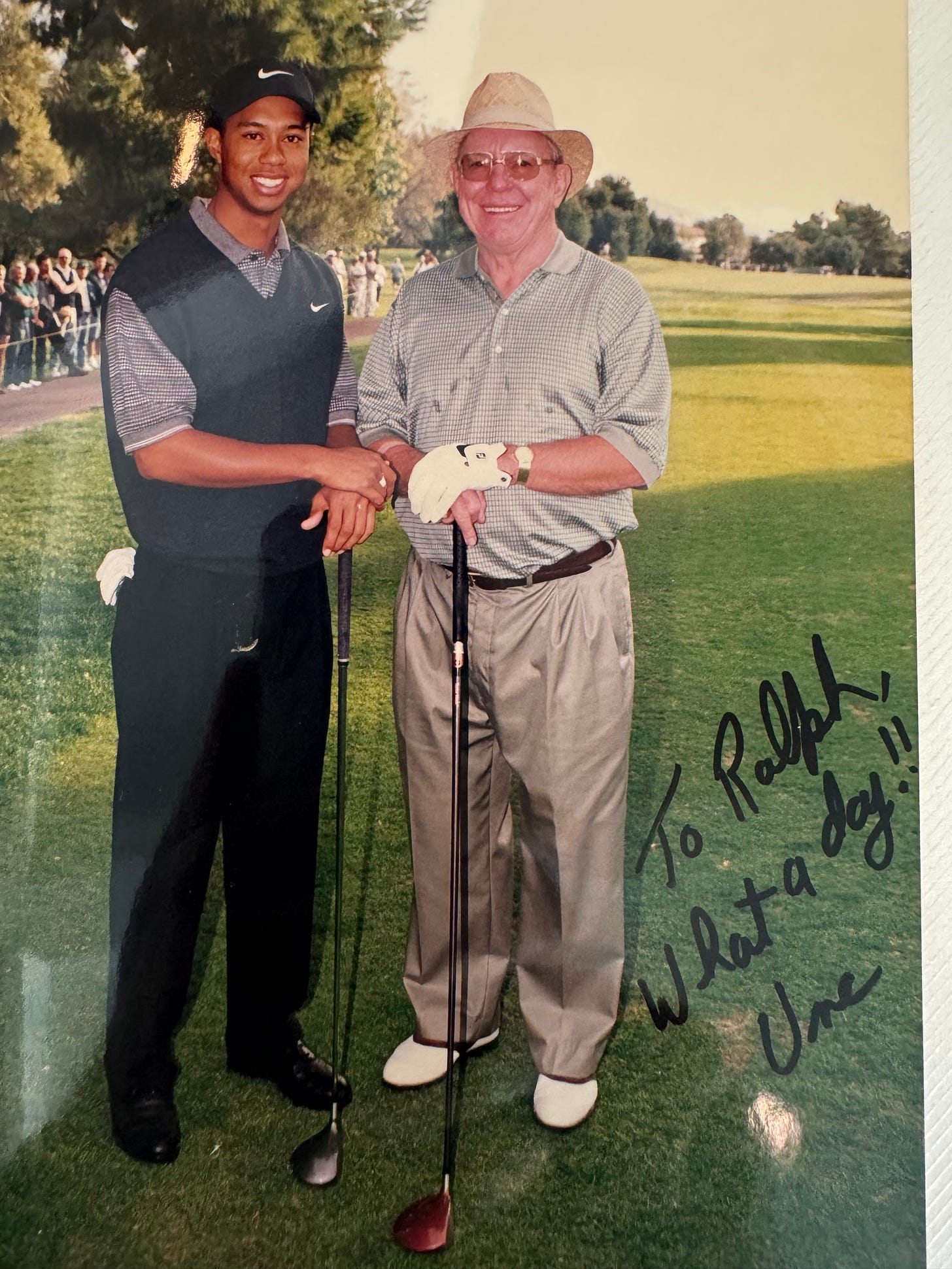

Me, Unk, and the lessons of Apple Computer

On my way back to Minnesota, I spend time in the Bay Area with my uncle, Herbert Carl Carlson. His brother George called him Herb. Everybody else called him Carl. I called him “Unk.” At the time, Unk was retired. Now he’s gone. I miss him so much.

In his day, Unk is a mechanical engineer by trade, with a head for how things work. Out of the Army, he punches the clock at Pioneer Engineering and then Honeywell in the Twin Cities. He moves to California in 1970 with my Aunt Rita and Cousin David and takes a job for a company with a new way to bind books. Puts all his savings into company stock. The whole thing crashes. He tells me at that time his net worth is maybe $10,000. Then he goes to work for a company called Computer Automation. I remember visiting him on vacation back in those days. Unk tries to explain binary code to me, but he has a better chance of getting me to open a biology textbook.

Fast-forward to the late-’70s. Unk gets a good job with BTI Computer Systems and plans out his retirement. This is it, he thinks. They like him, he likes them. Six months in, everything is good. Another 15 years or so and he’ll get that RV and travel the country. He likes the national parks.

Then comes a call from a headhunter who has heard about these two guys. They have this new way of looking at computers and the world and, dang it, Carl, you should go meet these guys. He’s 50 and settling in, but he never turns down the universe when it asks the question.

Long story short, Steve Jobs and his staff impress and are impressed and at the end of the meeting they decide that Carl Carlson will be Apple’s executive VP of manufacturing. Boom. Three years later, Unk retires, buys a big house, a small RV, and never puts on a tie again. And when his broken nephew shows up, he offers no unsolicited advice or judgment. He just takes me out on the golf course, plays gin rummy with me, and offers support and his own experience, strength and hope.

I mean, after nearly killing myself in LA, what can I do? I take Goddard’s advice and soak it up. I play golf and cards and swim in his pool and take Jacuzzis.

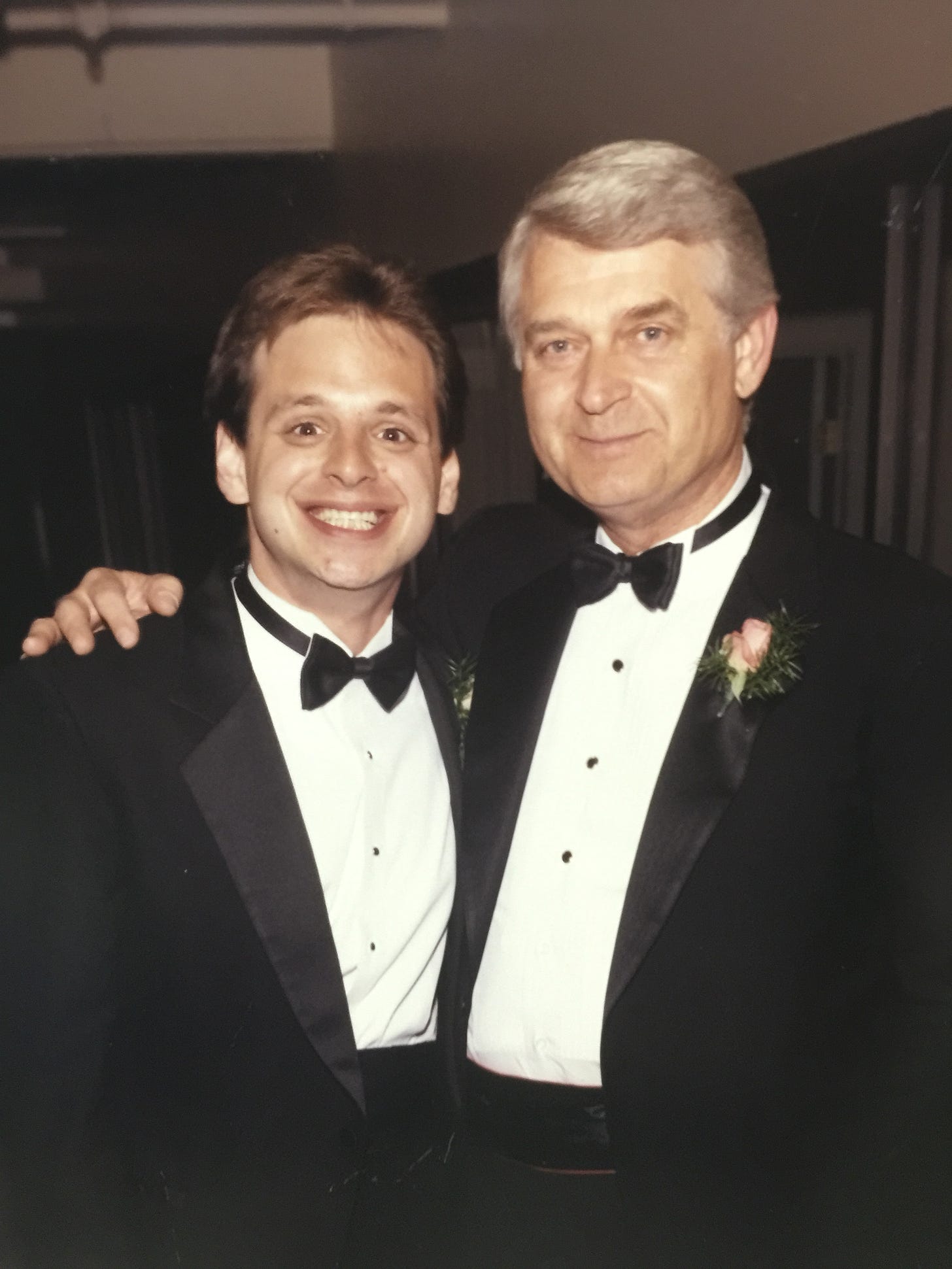

The World’s Greatest Salesman saves my life

In May of ’86, a couple of years after getting back to Minnesota, my adopted Uncle Jimmy, the greatest salesman I ever knew, sells me on the idea of going for a little 28-day retreat at the Hazelden Treatment Center in Center City. Says I can even bring my golf clubs. That’s funny only if you’ve actually been a patient there.

Jimmy Lupient came from nothing and had less after he was thrown out of high school for selling cigarettes. Then he gets a job as a lot boy at a Packard dealership. Then he rents a trailer on Central Avenue and has zero inventory but calls himself a car dealer. In a few short years, the Lupient name is hanging all over the Twin Cities and his empire includes real estate holdings and equipment companies throughout the Midwest.

“Ralphie Junior ... go to Hazelden — there’s a waiting list for a bed, but I got you a bed. It’s expen-sive, but I’ll write the check. And even though I know you’re going to do something else, you’ve got a job here waiting for you if you want it when you get out.”

Nobody plans to be a drug addict or an alcoholic. Ask me when I’m 10 years old what I wanted to be when I grew up, I say, “Oh, lots of things. I wanna be a sportscaster, and a game show host, and I wanna replace Johnny Carson, and I wanna be an actor on stage or in the movies, and I wanna write books and movies, and maybe some day be a teacher.”

Never would I say, “I wanna end up in rehab.” But here I am, at 25, in the bin with the heroin addicts and the acid casualties. I was a booze and blow and weed man. Even in treatment, there is a hierarchy.

So I get through it and get out and fix two thoughts squarely in my now-only-slightly-cleaned-up head. First, I own absolutely and without equivocation that my life will not improve if I drink or use drugs. Second, when the universe asks, I say “yes.”

LFG!

I call every high school and small-college game I can find, no matter what the sport, no matter what it pays. That last part really doesn’t figure in because almost all of them don’t pay a penny. But I take the gigs. I work on producing and hosting a cable show, The Minnesota Hockey Report. To make the rent, I produce video yearbooks and local sports highlight reels and some corporate industrial and training videos. My production experience in LA makes me more than just another pretty voice.

And I start to get breaks. This time, my eyes are open. I take risks. The universe asks, I say “yes.”

For a time, I’m the voice of a women’s professional volleyball team. Then they fold. Then I go audition for the American Wrestling Association, even though I’m not a huge fan of the sport at the time and had never attended a live match before I call one. But I do it. I jump at it. Then they fold.

Then comes the big break. It isn’t exactly the job I want, but I go for it anyway, with so much determination and force that either Norm Green’s gonna file a restraining order against me or give me the job. He gives me the job. As radio analyst and host.

Three years in Minnesota working with the North Stars. Sober seven years in1993. Unbelievable support system in place, and I’m living in a modest but comfortable condo. I’m doing well. I’ve dug out. Then Norm announces he’s moving the team to Texas. Almost everybody in the North Stars family balks or is turned away.

I could just stay in Minnesota. It’d be easy to get deterred by the frustrations of negotiating in a bipolar team structure — one group gone to Dallas with Norm, another group left to wrap up the season in Minnesota.

But I push forward. Hard. Eventually, I have to chase down Norm at his new home in Dallas. I’m at Unk’s house in California when I make the call in the spring of ’93.

“Norman, you can use me in Dallas. But if you want to start fresh, I get it. I don’t need a contract extension or anything like that. I’ll take you at your word. You want me there, I’m there.”

“I think you’ll be great here. Come to Texas with us.”

So I move to a new city, with no friends other than hockey players and coaches and a couple of staffers who jumped on the moving vans. And now, in a blink, it’s 25 years since my first game in the Stars’ booth. That’s 2,058 regular-season and playoff games since that first night.

There are so many intoxicants here that sometimes it’s hard to breathe. The juice you get in doing live games over a microphone is probably akin to the feeling a Wallenda gets when he steps out onto the wire. Being around the testosterone and competitive energy emanating from these high-achieving young men is like a daily dunking in the fountain of youth. Traveling on private charters, staying in luxury hotels, eating at the finest restaurants and earning a good buck can certainly make one … comfortable.

I’m proud of everything I’ve been a part of here, and nobody knows better than I what I’m walking away from. But I’m restless. Even dabbling in offseason acting and writing projects hasn’t quite scratched the itch.

So I go on, on my timetable and terms, looking for the next great adventure. There are no sure things about what’s ahead; I’ve left the guarantees behind me.

Ralphisming Number 1:

It’s a rainy October night, and the art cards have to be delivered to Andy Friendly’s Hollywood Hills estate before he leaves for the airport. John Ridgway’s running late with the designs, and I’m pacing in his office in the Trans-America Video building on Vine Street while checking my Thomas Guide map book for the route. He finishes up the artwork and puts it in a large envelope. Tells me to go and get there fast.

I urge an old Datsun 240z through the rain and LA’s rush-hour traffic, frantically glancing back and forth from my watch to the glum view of stopped cars through the spotted and cracked windshield. I’m stuck, dead in the middle of Hollywood Boulevard, right next to Mann’s Chinese Theatre. The sights are magnificent, even in the rain. I love Hollywood and am over the moon that at such a young age I’m actually working here in the television business. But nothing is happening. The view isn’t changing and I’m sitting in the same spot for what seems like a very long time.

It’s at that moment that I cut the wheel hard to the right and head up toward the hills, uncertain of where I’m going. But I decide — right then, right there — that for me it’s better to be moving freely in the wrong direction than standing still going forward.

Ralph, great story. Listening/reading hockey history(which it eventually became) is one of my greatest pastimes. I have been watching hockey since “Gump” Worsley was between the pipes for the Rangers. The duo of yourself and Razor was the all time greatest announcer team of any sport I have ever watched or listened to.

Thank You